Kubernetes Blog The Kubernetes blog is used by the project to communicate new features, community reports, and any news that might be relevant to the Kubernetes community.

-

Spotlight on SIG Architecture: API Governance

on February 12, 2026 at 12:00 am

This is the fifth interview of a SIG Architecture Spotlight series that covers the different subprojects, and we will be covering SIG Architecture: API Governance. In this SIG Architecture spotlight we talked with Jordan Liggitt, lead of the API Governance sub-project. Introduction FM: Hello Jordan, thank you for your availability. Tell us a bit about yourself, your role and how you got involved in Kubernetes. JL: My name is Jordan Liggitt. I’m a Christian, husband, father of four, software engineer at Google by day, and amateur musician by stealth. I was born in Texas (and still like to claim it as my point of origin), but I’ve lived in North Carolina for most of my life. I’ve been working on Kubernetes since 2014. At that time, I was working on authentication and authorization at Red Hat, and my very first pull request to Kubernetes attempted to add an OAuth server to the Kubernetes API server. It never exited work-in-progress status. I ended up going with a different approach that layered on top of the core Kubernetes API server in a different project (spoiler alert: this is foreshadowing), and I closed it without merging six months later. Undeterred by that start, I stayed involved, helped build Kubernetes authentication and authorization capabilities, and got involved in the definition and evolution of the core Kubernetes APIs from early beta APIs, like v1beta3 to v1. I got tagged as an API reviewer in 2016 based on those contributions, and was added as an API approver in 2017. Today, I help lead the API Governance and code organization subprojects for SIG Architecture, and I am a tech lead for SIG Auth. FM: And when did you get specifically involved in the API Governance project? JL: Around 2019. Goals and scope of API Governance FM: How would you describe the main goals and areas of intervention of the subproject? The surface area includes all the various APIs Kubernetes has, and there are APIs that people do not always realize are APIs: command-line flags, configuration files, how binaries are run, how they talk to back-end components like the container runtime, and how they persist data. People often think of “the API” as only the REST API… that is the biggest and most obvious one, and the one with the largest audience, but all of these other surfaces are also APIs. Their audiences are narrower, so there is more flexibility there, but they still require consideration. The goals are to be stable while still enabling innovation. Stability is easy if you never change anything, but that contradicts the goal of evolution and growth. So we balance “be stable” with “allow change”. FM: Speaking of changes, in terms of ensuring consistency and quality (which is clearly one of the reasons this project exists), what are the specific quality gates in the lifecycle of a Kubernetes change? Does API Governance get involved during the release cycle, prior to it through guidelines, or somewhere in between? At what points do you ensure the intended role is fulfilled? JL: We have guidelines and conventions, both for APIs in general and for how to change an API. These are living documents that we update as we encounter new scenarios. They are long and dense, so we also support them with involvement at either the design stage or the implementation stage. Sometimes, due to bandwidth constraints, teams move ahead with design work without feedback from API Review. That’s fine, but it means that when implementation begins, the API review will happen then, and there may be substantial feedback. So we get involved when a new API is created or an existing API is changed, either at design or implementation. FM: Is this during the Kubernetes Enhancement Proposal (KEP) process? Since KEPs are mandatory for enhancements, I assume part of the work intersects with API Governance? JL: It can. KEPs vary in how detailed they are. Some include literal API definitions. When they do, we can perform an API review at the design stage. Then implementation becomes a matter of checking fidelity to the design. Getting involved early is ideal. But some KEPs are conceptual and leave details to the implementation. That’s not wrong; it just means the implementation will be more exploratory. Then API Review gets involved later, possibly recommending structural changes. There’s a trade-off regardless: detailed design upfront versus iterative discovery during implementation. People and teams work differently, and we’re flexible and happy to consult early or at implementation time. FM: This reminds me of what Fred Brooks wrote in “The Mythical Man-Month” about conceptual integrity being central to product quality… No matter how you structure the process, there must be a point where someone looks at what is coming and ensures conceptual integrity. Kubernetes uses APIs everywhere — externally and internally — so API Governance is critical to maintaining that integrity. How is this captured? JL: Yes, the conventions document captures patterns we’ve learned over time: what to do in various situations. We also have automated linters and checks to ensure correctness around patterns like spec/status semantics. These automated tools help catch issues even when humans miss them. As new scenarios arise — and they do constantly — we think through how to approach them and fold the results back into our documentation and tools. Sometimes it takes a few attempts before we settle on an approach that works well. FM: Exactly. Each new interaction improves the guidelines. JL: Right. And sometimes the first approach turns out to be wrong. It may take two or three iterations before we land on something robust. The impact of Custom Resource Definitions FM: Is there any particular change, episode, or domain that stands out as especially noteworthy, complex, or interesting in your experience? JL: The watershed moment was Custom Resources. Prior to that, every API was handcrafted by us and fully reviewed. There were inconsistencies, but we understood and controlled every type and field. When Custom Resources arrived, anyone could define anything. The first version did not even require a schema. That made it extremely powerful — it enabled change immediately — but it left us playing catch-up on stability and consistency. When Custom Resources graduated to General Availability (GA), schemas became required, but escape hatches still existed for backward compatibility. Since then, we’ve been working on giving CRD authors validation capabilities comparable to built-ins. Built-in validation rules for CRDs have only just reached GA in the last few releases. So CRDs opened the “anything is possible” era. Built-in validation rules are the second major milestone: bringing consistency back. The three major themes have been defining schemas, validating data, and handling pre-existing invalid data. With ratcheting validation (allowing data to improve without breaking existing objects), we can now guide CRD authors toward conventions without breaking the world. API Governance in context FM: How does API Governance relate to SIG Architecture and API Machinery? JL: API Machinery provides the actual code and tools that people build APIs on. They don’t review APIs for storage, networking, scheduling, etc. SIG Architecture sets the overall system direction and works with API Machinery to ensure the system supports that direction. API Governance works with other SIGs building on that foundation to define conventions and patterns, ensuring consistent use of what API Machinery provides. FM: Thank you. That clarifies the flow. Going back to release cycles: do release phases — enhancements freeze, code freeze — change your workload? Or is API Governance mostly continuous? JL: We get involved in two places: design and implementation. Design involvement increases before enhancements freeze; implementation involvement increases before code freeze. However, many efforts span multiple releases, so there is always some design and implementation happening, even for work targeting future releases. Between those intense periods, we often have time to work on long-term design work. An anti-pattern we see is teams thinking about a large feature for months and then presenting it three weeks before enhancements freeze, saying, “Here is the design, please review.” For big changes with API impact, it’s much better to involve API Governance early. And there are good times in the cycle for this — between freezes — when people have bandwidth. That’s when long-term review work fits best. Getting involved FM: Clearly. Now, regarding team dynamics and new contributors: how can someone get involved in API Governance? What should they focus on? JL: It’s usually best to follow a specific change rather than trying to learn everything at once. Pick a small API change, perhaps one someone else is making or one you want to make, and observe the full process: design, implementation, review. High-bandwidth review — live discussion over video — is often very effective. If you’re making or following a change, ask whether there’s a time to go over the design or PR together. Observing those discussions is extremely instructive. Start with a small change. Then move to a bigger one. Then maybe a new API. That builds understanding of conventions as they are applied in practice. FM: Excellent. Any final comments, or anything we missed? JL: Yes… the reason we care so much about compatibility and stability is for our users. It’s easy for contributors to see those requirements as painful obstacles preventing cleanup or requiring tedious work… but users integrated with our system, and we made a promise to them: we want them to trust that we won’t break that contract. So even when it requires more work, moves slower, or involves duplication, we choose stability. We are not trying to be obstructive; we are trying to make life good for users. A lot of our questions focus on the future: you want to do something now… how will you evolve it later without breaking it? We assume we will know more in the future, and we want the design to leave room for that. We also assume we will make mistakes. The question then is: how do we leave ourselves avenues to improve while keeping compatibility promises? FM: Exactly. Jordan, thank you, I think we’ve covered everything. This has been an insightful view into the API Governance project and its role in the wider Kubernetes project. JL: Thank you.

-

Introducing Node Readiness Controller

on February 3, 2026 at 2:00 am

In the standard Kubernetes model, a node’s suitability for workloads hinges on a single binary “Ready” condition. However, in modern Kubernetes environments, nodes require complex infrastructure dependencies—such as network agents, storage drivers, GPU firmware, or custom health checks—to be fully operational before they can reliably host pods. Today, on behalf of the Kubernetes project, I am announcing the Node Readiness Controller. This project introduces a declarative system for managing node taints, extending the readiness guardrails during node bootstrapping beyond standard conditions. By dynamically managing taints based on custom health signals, the controller ensures that workloads are only placed on nodes that met all infrastructure-specific requirements. Why the Node Readiness Controller? Core Kubernetes Node “Ready” status is often insufficient for clusters with sophisticated bootstrapping requirements. Operators frequently struggle to ensure that specific DaemonSets or local services are healthy before a node enters the scheduling pool. The Node Readiness Controller fills this gap by allowing operators to define custom scheduling gates tailored to specific node groups. This enables you to enforce distinct readiness requirements across heterogeneous clusters, ensuring for example, that GPU equipped nodes only accept pods once specialized drivers are verified, while general purpose nodes follow a standard path. It provides three primary advantages: Custom Readiness Definitions: Define what ready means for your specific platform. Automated Taint Management: The controller automatically applies or removes node taints based on condition status, preventing pods from landing on unready infrastructure. Declarative Node Bootstrapping: Manage multi-step node initialization reliably, with a clear observability into the bootstrapping process. Core concepts and features The controller centers around the NodeReadinessRule (NRR) API, which allows you to define declarative gates for your nodes. Flexible enforcement modes The controller supports two distinct operational modes: Continuous enforcement Actively maintains the readiness guarantee throughout the node’s entire lifecycle. If a critical dependency (like a device driver) fails later, the node is immediately tainted to prevent new scheduling. Bootstrap-only enforcement Specifically for one-time initialization steps, such as pre-pulling heavy images or hardware provisioning. Once conditions are met, the controller marks the bootstrap as complete and stops monitoring that specific rule for the node. Condition reporting The controller reacts to Node Conditions rather than performing health checks itself. This decoupled design allows it to integrate seamlessly with other tools existing in the ecosystem as well as custom solutions: Node Problem Detector (NPD): Use existing NPD setups and custom scripts to report node health. Readiness Condition Reporter: A lightweight agent provided by the project that can be deployed to periodically check local HTTP endpoints and patch node conditions accordingly. Operational safety with dry run Deploying new readiness rules across a fleet carries inherent risk. To mitigate this, dry run mode allows operators to first simulate impact on the cluster. In this mode, the controller logs intended actions and updates the rule’s status to show affected nodes without applying actual taints, enabling safe validation before enforcement. Example: CNI bootstrapping The following NodeReadinessRule ensures a node remains unschedulable until its CNI agent is functional. The controller monitors a custom cniplugin.example.net/NetworkReady condition and only removes the readiness.k8s.io/acme.com/network-unavailable taint once the status is True. apiVersion: readiness.node.x-k8s.io/v1alpha1 kind: NodeReadinessRule metadata: name: network-readiness-rule spec: conditions: – type: “cniplugin.example.net/NetworkReady” requiredStatus: “True” taint: key: “readiness.k8s.io/acme.com/network-unavailable” effect: “NoSchedule” value: “pending” enforcementMode: “bootstrap-only” nodeSelector: matchLabels: node-role.kubernetes.io/worker: “” Demo: Getting involved The Node Readiness Controller is just getting started, with our initial releases out, and we are seeking community feedback to refine the roadmap. Following our productive Unconference discussions at KubeCon NA 2025, we are excited to continue the conversation in person. Join us at KubeCon + CloudNativeCon Europe 2026 for our maintainer track session: Addressing Non-Deterministic Scheduling: Introducing the Node Readiness Controller. In the meantime, you can contribute or track our progress here: GitHub: https://sigs.k8s.io/node-readiness-controller Slack: Join the conversation in #sig-node-readiness-controller Documentation: Getting Started

-

New Conversion from cgroup v1 CPU Shares to v2 CPU Weight

on January 30, 2026 at 4:00 pm

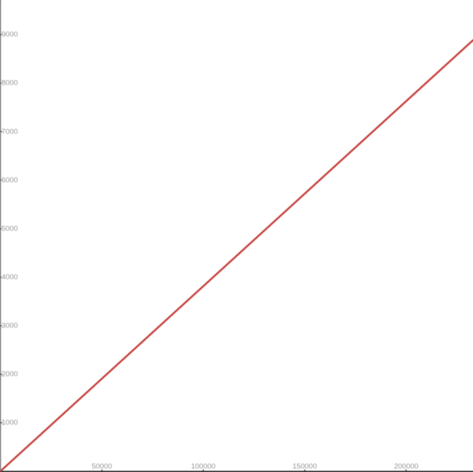

I’m excited to announce the implementation of an improved conversion formula from cgroup v1 CPU shares to cgroup v2 CPU weight. This enhancement addresses critical issues with CPU priority allocation for Kubernetes workloads when running on systems with cgroup v2. Background Kubernetes was originally designed with cgroup v1 in mind, where CPU shares were defined simply by assigning the container’s CPU requests in millicpu form. For example, a container requesting 1 CPU (1024m) would get (cpu.shares = 1024). After a while, cgroup v1 started being replaced by its successor, cgroup v2. In cgroup v2, the concept of CPU shares (which ranges from 2 to 262144, or from 2¹ to 2¹⁸) was replaced with CPU weight (which ranges from [1, 10000], or 10⁰ to 10⁴). With the transition to cgroup v2, KEP-2254 introduced a conversion formula to map cgroup v1 CPU shares to cgroup v2 CPU weight. The conversion formula was defined as: cpu.weight = (1 + ((cpu.shares – 2) * 9999) / 262142) This formula linearly maps values from [2¹, 2¹⁸] to [10⁰, 10⁴]. While this approach is simple, the linear mapping imposes a few significant problems and impacts both performance and configuration granularity. Problems with previous conversion formula The current conversion formula creates two major issues: 1. Reduced priority against non-Kubernetes workloads In cgroup v1, the default value for CPU shares is 1024, meaning a container requesting 1 CPU has equal priority with system processes that live outside of Kubernetes’ scope. However, in cgroup v2, the default CPU weight is 100, but the current formula converts 1 CPU (1024m) to only ≈39 weight – less than 40% of the default. Example: Container requesting 1 CPU (1024m) cgroup v1: cpu.shares = 1024 (equal to default) cgroup v2 (current): cpu.weight = 39 (much lower than default 100) This means that after moving to cgroup v2, Kubernetes (or OCI) workloads would de-facto reduce their CPU priority against non-Kubernetes processes. The problem can be severe for setups with many system daemons that run outside of Kubernetes’ scope and expect Kubernetes workloads to have priority, especially in situations of resource starvation. 2. Unmanageable granularity The current formula produces very low values for small CPU requests, limiting the ability to create sub-cgroups within containers for fine-grained resource distribution (which will possibly be much easier moving forward, see KEP #5474 for more info). Example: Container requesting 100m CPU cgroup v1: cpu.shares = 102 cgroup v2 (current): cpu.weight = 4 (too low for sub-cgroup configuration) With cgroup v1, requesting 100m CPU which led to 102 CPU shares was manageable in the sense that sub-cgroups could have been created inside the main container, assigning fine-grained CPU priorities for different groups of processes. With cgroup v2 however, having 4 shares is very hard to distribute between sub-cgroups since it’s not granular enough. With plans to allow writable cgroups for unprivileged containers, this becomes even more relevant. New conversion formula Description The new formula is more complicated, but does a much better job mapping between cgroup v1 CPU shares and cgroup v2 CPU weight: $$cpu.weight = \lceil 10^{(L^{2}/612 + 125L/612 – 7/34)} \rceil, \text{ where: } L = \log_2(cpu.shares)$$The idea is that this is a quadratic function to cross the following values: (2, 1): The minimum values for both ranges. (1024, 100): The default values for both ranges. (262144, 10000): The maximum values for both ranges. Visually, the new function looks as follows: And if you zoom in to the important part: The new formula is “close to linear”, yet it is carefully designed to map the ranges in a clever way so the three important points above would cross. How it solves the problems Better priority alignment: A container requesting 1 CPU (1024m) will now get a cpu.weight = 102. This value is close to cgroup v2’s default 100. This restores the intended priority relationship between Kubernetes workloads and system processes. Improved granularity: A container requesting 100m CPU will get cpu.weight = 17, (see here). Enables better fine-grained resource distribution within containers. Adoption and integration This change was implemented at the OCI layer. In other words, this is not implemented in Kubernetes itself; therefore the adoption of the new conversion formula depends solely on the OCI runtime adoption. For example: runc: The new formula is enabled from version 1.3.2. crun: The new formula is enabled from version 1.23. Impact on existing deployments Important: Some consumers may be affected if they assume the older linear conversion formula. Applications or monitoring tools that directly calculate expected CPU weight values based on the previous formula may need updates to account for the new quadratic conversion. This is particularly relevant for: Custom resource management tools that predict CPU weight values. Monitoring systems that validate or expect specific weight values. Applications that programmatically set or verify CPU weight values. The Kubernetes project recommends testing the new conversion formula in non-production environments before upgrading OCI runtimes to ensure compatibility with existing tooling. Where can I learn more? For those interested in this enhancement: Kubernetes GitHub Issue #131216 – Detailed technical analysis and examples, including discussions and reasoning for choosing the above formula. KEP-2254: cgroup v2 – Original cgroup v2 implementation in Kubernetes. Kubernetes cgroup documentation – Current resource management guidance. How do I get involved? For those interested in getting involved with Kubernetes node-level features, join the Kubernetes Node Special Interest Group. We always welcome new contributors and diverse perspectives on resource management challenges.

-

Ingress NGINX: Statement from the Kubernetes Steering and Security Response Committees

on January 29, 2026 at 12:00 am

In March 2026, Kubernetes will retire Ingress NGINX, a piece of critical infrastructure for about half of cloud native environments. The retirement of Ingress NGINX was announced for March 2026, after years of public warnings that the project was in dire need of contributors and maintainers. There will be no more releases for bug fixes, security patches, or any updates of any kind after the project is retired. This cannot be ignored, brushed off, or left until the last minute to address. We cannot overstate the severity of this situation or the importance of beginning migration to alternatives like Gateway API or one of the many third-party Ingress controllers immediately. To be abundantly clear: choosing to remain with Ingress NGINX after its retirement leaves you and your users vulnerable to attack. None of the available alternatives are direct drop-in replacements. This will require planning and engineering time. Half of you will be affected. You have two months left to prepare. Existing deployments will continue to work, so unless you proactively check, you may not know you are affected until you are compromised. In most cases, you can check to find out whether or not you rely on Ingress NGINX by running kubectl get pods –all-namespaces –selector app.kubernetes.io/name=ingress-nginx with cluster administrator permissions. Despite its broad appeal and widespread use by companies of all sizes, and repeated calls for help from the maintainers, the Ingress NGINX project never received the contributors it so desperately needed. According to internal Datadog research, about 50% of cloud native environments currently rely on this tool, and yet for the last several years, it has been maintained solely by one or two people working in their free time. Without sufficient staffing to maintain the tool to a standard both ourselves and our users would consider secure, the responsible choice is to wind it down and refocus efforts on modern alternatives like Gateway API. We did not make this decision lightly; as inconvenient as it is now, doing so is necessary for the safety of all users and the ecosystem as a whole. Unfortunately, the flexibility Ingress NGINX was designed with, that was once a boon, has become a burden that cannot be resolved. With the technical debt that has piled up, and fundamental design decisions that exacerbate security flaws, it is no longer reasonable or even possible to continue maintaining the tool even if resources did materialize. We issue this statement together to reinforce the scale of this change and the potential for serious risk to a significant percentage of Kubernetes users if this issue is ignored. It is imperative that you check your clusters now. If you are reliant on Ingress NGINX, you must begin planning for migration. Thank you, Kubernetes Steering Committee Kubernetes Security Response Committee

-

Experimenting with Gateway API using kind

on January 28, 2026 at 12:00 am

This document will guide you through setting up a local experimental environment with Gateway API on kind. This setup is designed for learning and testing. It helps you understand Gateway API concepts without production complexity. Caution:This is an experimentation learning setup, and should not be used for production. The components used on this document are not suited for production usage. Once you’re ready to deploy Gateway API in a production environment, select an implementation that suits your needs. Overview In this guide, you will: Set up a local Kubernetes cluster using kind (Kubernetes in Docker) Deploy cloud-provider-kind, which provides both LoadBalancer Services and a Gateway API controller Create a Gateway and HTTPRoute to route traffic to a demo application Test your Gateway API configuration locally This setup is ideal for learning, development, and experimentation with Gateway API concepts. Prerequisites Before you begin, ensure you have the following installed on your local machine: Docker – Required to run kind and cloud-provider-kind kubectl – The Kubernetes command-line tool kind – Kubernetes in Docker curl – Required to test the routes Create a kind cluster Create a new kind cluster by running: kind create cluster This will create a single-node Kubernetes cluster running in a Docker container. Install cloud-provider-kind Next, you need cloud-provider-kind, which provides two key components for this setup: A LoadBalancer controller that assigns addresses to LoadBalancer-type Services A Gateway API controller that implements the Gateway API specification It also automatically installs the Gateway API Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) in your cluster. Run cloud-provider-kind as a Docker container on the same host where you created the kind cluster: VERSION=”$(basename $(curl -s -L -o /dev/null -w ‘%{url_effective}’ https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/cloud-provider-kind/releases/latest))” docker run -d –name cloud-provider-kind –rm –network host -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock registry.k8s.io/cloud-provider-kind/cloud-controller-manager:${VERSION} Note: On some systems, you may need elevated privileges to access the Docker socket. Verify that cloud-provider-kind is running: docker ps –filter name=cloud-provider-kind You should see the container listed and in a running state. You can also check the logs: docker logs cloud-provider-kind Experimenting with Gateway API Now that your cluster is set up, you can start experimenting with Gateway API resources. cloud-provider-kind automatically provisions a GatewayClass called cloud-provider-kind. You’ll use this class to create your Gateway. It is worth noticing that while kind is not a cloud provider, the project is named as cloud-provider-kind as it provides features that simulate a cloud-enabled environment. Deploy a Gateway The following manifest will: Create a new namespace called gateway-infra Deploy a Gateway that listens on port 80 Accept HTTPRoutes with hostnames matching the *.exampledomain.example pattern Allow routes from any namespace to attach to the Gateway. Note: In real clusters, prefer Same or Selector values on the allowedRoutes namespace selector field to limit attachments. Apply the following manifest: — apiVersion: v1 kind: Namespace metadata: name: gateway-infra — apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1 kind: Gateway metadata: name: gateway namespace: gateway-infra spec: gatewayClassName: cloud-provider-kind listeners: – name: default hostname: “*.exampledomain.example” port: 80 protocol: HTTP allowedRoutes: namespaces: from: All Then verify that your Gateway is properly programmed and has an address assigned: kubectl get gateway -n gateway-infra gateway Expected output: NAME CLASS ADDRESS PROGRAMMED AGE gateway cloud-provider-kind 172.18.0.3 True 5m6s The PROGRAMMED column should show True, and the ADDRESS field should contain an IP address. Deploy a demo application Next, deploy a simple echo application that will help you test your Gateway configuration. This application: Listens on port 3000 Echoes back request details including path, headers, and environment variables Runs in a namespace called demo Apply the following manifest: apiVersion: v1 kind: Namespace metadata: name: demo — apiVersion: v1 kind: Service metadata: labels: app.kubernetes.io/name: echo name: echo namespace: demo spec: ports: – name: http port: 3000 protocol: TCP targetPort: 3000 selector: app.kubernetes.io/name: echo type: ClusterIP — apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: Deployment metadata: labels: app.kubernetes.io/name: echo name: echo namespace: demo spec: selector: matchLabels: app.kubernetes.io/name: echo template: metadata: labels: app.kubernetes.io/name: echo spec: containers: – env: – name: POD_NAME valueFrom: fieldRef: apiVersion: v1 fieldPath: metadata.name – name: NAMESPACE valueFrom: fieldRef: apiVersion: v1 fieldPath: metadata.namespace image: registry.k8s.io/gateway-api/echo-basic:v20251204-v1.4.1 name: echo-basic Create an HTTPRoute Now create an HTTPRoute to route traffic from your Gateway to the echo application. This HTTPRoute will: Respond to requests for the hostname some.exampledomain.example Route traffic to the echo application Attach to the Gateway in the gateway-infra namespace Apply the following manifest: apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1 kind: HTTPRoute metadata: name: echo namespace: demo spec: parentRefs: – name: gateway namespace: gateway-infra hostnames: [“some.exampledomain.example”] rules: – matches: – path: type: PathPrefix value: / backendRefs: – name: echo port: 3000 Test your route The final step is to test your route using curl. You’ll make a request to the Gateway’s IP address with the hostname some.exampledomain.example. The command below is for POSIX shell only, and may need to be adjusted for your environment: GW_ADDR=$(kubectl get gateway -n gateway-infra gateway -o jsonpath='{.status.addresses[0].value}’) curl –resolve some.exampledomain.example:80:${GW_ADDR} http://some.exampledomain.example You should receive a JSON response similar to this: { “path”: “/”, “host”: “some.exampledomain.example”, “method”: “GET”, “proto”: “HTTP/1.1”, “headers”: { “Accept”: [ “*/*” ], “User-Agent”: [ “curl/8.15.0” ] }, “namespace”: “demo”, “ingress”: “”, “service”: “”, “pod”: “echo-dc48d7cf8-vs2df” } If you see this response, congratulations! Your Gateway API setup is working correctly. Troubleshooting If something isn’t working as expected, you can troubleshoot by checking the status of your resources. Check the Gateway status First, inspect your Gateway resource: kubectl get gateway -n gateway-infra gateway -o yaml Look at the status section for conditions. Your Gateway should have: Accepted: True – The Gateway was accepted by the controller Programmed: True – The Gateway was successfully configured .status.addresses populated with an IP address Check the HTTPRoute status Next, inspect your HTTPRoute: kubectl get httproute -n demo echo -o yaml Check the status.parents section for conditions. Common issues include: ResolvedRefs set to False with reason BackendNotFound; this means that the backend Service doesn’t exist or has the wrong name Accepted set to False; this means that the route couldn’t attach to the Gateway (check namespace permissions or hostname matching) Example error when a backend is not found: status: parents: – conditions: – lastTransitionTime: “2026-01-19T17:13:35Z” message: backend not found observedGeneration: 2 reason: BackendNotFound status: “False” type: ResolvedRefs controllerName: kind.sigs.k8s.io/gateway-controller Check controller logs If the resource statuses don’t reveal the issue, check the cloud-provider-kind logs: docker logs -f cloud-provider-kind This will show detailed logs from both the LoadBalancer and Gateway API controllers. Cleanup When you’re finished with your experiments, you can clean up the resources: Remove Kubernetes resources Delete the namespaces (this will remove all resources within them): kubectl delete namespace gateway-infra kubectl delete namespace demo Stop cloud-provider-kind Stop and remove the cloud-provider-kind container: docker stop cloud-provider-kind Because the container was started with the –rm flag, it will be automatically removed when stopped. Delete the kind cluster Finally, delete the kind cluster: kind delete cluster Next steps Now that you’ve experimented with Gateway API locally, you’re ready to explore production-ready implementations: Production Deployments: Review the Gateway API implementations to find a controller that matches your production requirements Learn More: Explore the Gateway API documentation to learn about advanced features like TLS, traffic splitting, and header manipulation Advanced Routing: Experiment with path-based routing, header matching, request mirroring and other features following Gateway API user guides A final word of caution This kind setup is for development and learning only. Always use a production-grade Gateway API implementation for real workloads.